A Hawaiian Rebirth

Strong feelings of ethnic identity and the desire for legal rights among Native Hawaiians have grown since statehood. This movement came to be called the “Hawaiian Renaissance.” It sparked a widespread renewed interest in Hawaiian culture, land rights, and history. Although King Kalākaua was responsible for a cultural renaissance when he brought back traditional Hawaiian chant and hula, a stronger push came in the early 1970s. It grew with the fight to get Kaho‘olawe back from the U.S. Navy and with the battle over who has the right to govern, called sovereignty.

In 1976 the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana started working to get the federal government and the navy to stop the bombing of this island. They were so successful that, by 1994, not only had the bombing stopped, but Kaho‘olawe was also returned to the people of Hawai‘i.

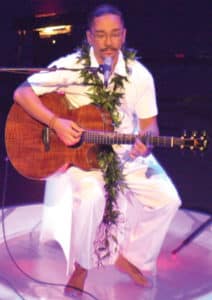

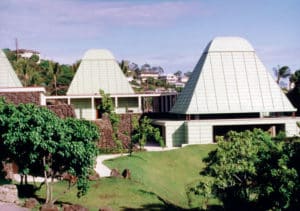

The Hawaiian movement also started Hawaiian “immersion” schools, where every subject is taught in the Hawaiian language. The University of Hawai‘i built a new Hawaiian Studies Center in 1996, and more people are studying Hawaiian language and culture than ever before. All schools have courses, classes, or units in Hawaiian history and culture. The 1978 Constitutional Convention promoted Hawaiian studies and set up the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Hawaiian, once again, became the official language of the islands, along with English. The Hawaiian political movement has been so strong that, in 1993, the U.S. government under President Clinton apologized to the Hawaiian people for the illegal overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1893. This formal statement was called the Apology Resolution.

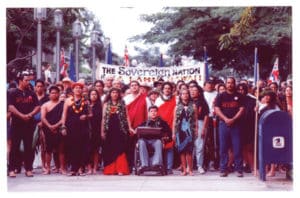

In January of 1993, the centennial of the overthrow of the monarchy brought out many feelings of both anger and solidarity among Native Hawaiians and others who supported their cause. Governor Waihe‘e ordered the Hawaiian flag to be flown at half-mast for five days during the centennial. President Clinton’s apology did not include any kind of payment for the taking of land or for the Hawaiian people who had suffered since the overthrow. Since then, Hawaiian groups have continued to fight for sovereignty, the right to control and rule their own land.

Senator Daniel Akaka for many years has tried to get what is known as the Akaka Bill passed in the U.S. Congress to give Native Hawaiians sovereign rights similar to those that Native Americans have. The Akaka Bill has been brought up before the House of Representatives in different versions, but as of 2011 has not had a full Senate vote. There are opponents to the bill from different sides. Some people say that Native Hawaiians would receive special treatment, or racial preference, and that this would be unconstitutional. Others think the bill would not go far enough in giving Native Hawaiians sovereignty, especially since the United States had already formally apologized for overthrowing the Hawaiian monarchy. In May of 2011, the Hawai‘i State House and Senate agreed that the state should recognize Native Hawaiians as indigenous people, a step toward national recognition as such.

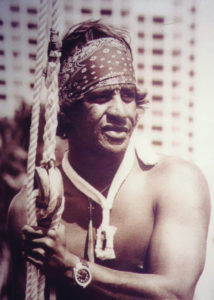

Another important and ongoing project begun in the 1970s was the Polynesian Voyaging Society, particularly their launching of the traditional Hawaiian sailing canoe called the Hōkūle‘a. Its voyages began with a historic trip to Tahiti in 1976. Hawaiian navigators wanted to retrace the route their ancestors took when they migrated to Hawai‘i over 1,500 years ago. In addition, they wanted to use traditional navigation methods, versus Western instruments. They built a replica of the double-hulled canoe used in ancient times and continue to have many successful voyages all over the Pacific. The Hōkūle‘a has become the most visible symbol of the Hawaiian renaissance.

One of the most remembered voyagers on the Hōkūle‘a was Eddie Aikau, the famous big wave surfer. On the ill fated 1978 trip, Aikau set out for help by paddling his surfboard to Lāna‘i. The canoe had begun to leak in one of its hulls and then capsized. Aikau was never found. Today, the saying “Eddie Would Go” refers to his ability to surf giant waves and to his heroic trip alone to find help to rescue those stranded on the Hōkūle‘a. Every year, if the waves are big enough, “the Eddie” surf contest is held on the North Shore of O‘ahu.